The ability to understand and generate novel sentences is the primary hallmark of human languages. Using finite means, a competent speaker can process an infinite number of signals which are themselves at the basis of fundamental human activities, from communicating complex instructions to telling stories, from expressing feelings to building scientific theories. Linguists refer to this phenomenon as the productivity of language, and they posit a specific mechanism as the driving force of that phenomenon: compositionality.

It might seem, then, that understanding compositionality would entail understanding the creative power of language. Given those high stakes, it is no wonder that the notion has received, and continues to receive, extensive attention from linguistics, philosophy, computer science and artificial intelligence. Strangely enough, though, it has also remained ill-defined and paradoxical, in spite of the extraordinary body of work that has been dedicated to it.

The problem is that compositionality is more than what it seems to be. If compositionality simply allowed complexity to emerge from simplicity, the question would have been settled long ago. Zadrozny (1994), in fact, points out that under such a vague requirement, any semantics can be encoded as being compositional, making the concept of compositionality itself vacuous. The real problem is that language does productivity in a very particular way, and it remains unclear how.

Reading the literature on compositionality makes it quickly obvious that specific theories are driven by different beliefs about the nature of language, in other words, by wider research questions. Being aware of such questions is helpful to understand why the topic is so hard to pin down. It may also provide fresh ideas, or simply the relief of knowing that compositionality does not have to be tackled entirely in one go.

My goal in this post is to review the tenets of classic work on compositionality, and to highlight how each theory has evolved to match particular theoretical positions about the nature of language. I will specifically discuss three such positions: a) language is innate; b) natural languages are formal languages; c) language is inseparable from context.

The many facets of compositionality

Two principles are usually mentioned under the heading compositionality, both (possibly incorrectly) attributed to Frege (see Pelletier's ‘Did Frege believe in Frege's principle?’, 2001):

- Bottom-up, the actual compositionality principle: "... an important general principle which we shall discuss later under the name Frege's Principle, that the meaning of the whole sentence is a function of the meanings of its parts." Cresswell (1973)

- Top-down, the context principle: "[I]t's a famous Fregean view that words have meaning only as constituents of (hence, presumably, only in virtue of their use in) sentences." (Fodor and LePore, 1992)

Obviously, the two principles are at odds. The compositionality principle says that the meaning of the sentence Dogs sleep is made of the meaning of dogs and the meaning of sleep. The context principle says that the meaning of dogs and the meaning of sleep depend on the meaning of Dogs sleep. As a frustrated Fodor puts it, "Something’s gotta give". (Fodor 2003 : 96-7)

So what exactly is compositionality? Where does it start, where does it stop? Does it really include both principles above? No one knows. In a 1984 piece dedicated to the phenomenon, Barbara Partee declares : "Given the extreme theory-dependence of the compositionality principle and the diversity of existing (pieces of) theories, it would be hopeless to try to enumerate all its possible versions."

Partee however also points out that if it is impossible to clearly define compositionality, we can fruitfully attempt to pinpoint the latent features of the phenomenon. This is the advice I will follow in the rest of this post, building upon a historical overview which covers three main approaches embodied in the work of a) Jerrold J. Katz and Jerry A. Fodor; b) Richard Montague; c) Charles J. Fillmore. As we will see, each theory approaches language in its own way, and it would be misguided to look for their respective definitions of compositionality independently from their core assumptions about what linguistics is and does.

Katz and Fodor. The question of innateness.

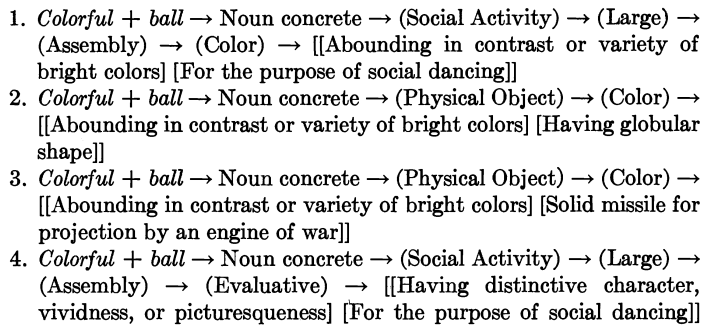

The first use of the term compositionality is to be found in Katz and Fodor (1963): ‘As a rule, the meaning of a word is a compositional function of the meanings of its parts, and we would like to be able to capture this compositionality.’ Katz and Fodor are inspired by Chomsky's distinction between 'competence' and 'performance', that is, the difference between 'knowing one's language' and 'using one's language'. In their paper, they specifically attempt to adapt the notion of competence to the area of semantics. Their main concern is the bottom-up principle, which they call the Projection Problem. They propose that semantics follows grammar rule-by-rule, according to an amalgamation process, where ‘amalgamation' is ‘the joining of elements from different sets of paths under a given grammatical marker if these elements satisfy the appropriate selection restrictions’. In simpler terms, they are looking for semantic rules which would tell us which senses of which words can be combined together to form a felicitous utterance. Those rules are encoded in the lexicon, and mastery of the lexicon is, in Chomskian fashion, a psychological competence.

What is that psychological competence good for? Katz and Fodor want a speaker to first be able to deal with certain lexical ambiguities that are left unresolved by syntax, and secondly produce acceptability judgements in accordance with the rest of his/her linguistic community. In other words, they posit selectional constraints encoded in the lexicon, which regulate both ambiguity and semantic felicity. Lexical competence allows the speaker to correctly understand the meaning of bill in My restaurant’s bill is large vs My bird’s bill is large. It also ensures the speaker will raise their eyebrows at The paint is silent, or indeed at the famous Colorless green ideas sleep furiously.

Beyond those selectional effects, they posit that semantics – like syntax – is a competence which does not use ‘information about setting’ and is ‘independent of individual differences between speakers’. In other words, context is not a relevant notion. As we will see later, this clearly separates them from other theorists (and of course, from most current work in Natural Language Processing).

To better understand the assumptions behind the Fodor and Katz approach, we must ask why Chomskian compositionality is the way it is, and we must come back to the question that is foundational to the theory. In 1959, Chomsky writes a damning review of Skinner's book Verbal behaviour (1957). Skinner is an empiricist who believes that knowing one's language involves having a set of verbal dispositions (saying things in response to stimuli) which are acquired by conditioning. Chomsky makes several arguments against Skinner, including the famous poverty of the stimulus. Specifically, Chomsky questions how children acquire their language so rapidly, particularly in cases where environmental information is sparse.

"The fact that all normal children acquire essentially comparable grammars of great complexity with remarkable rapidity suggests that human beings are somehow specially designed to do this, with data-handling or “hypothesis-formulating” ability of unknown character and complexity." (p. 57)

On the matter of compositionality, he also contends that “composition and production of an utterance is not simply a matter of stringing together a sequence of responses under the control of outside stimulation” (p. 55). That is, sentences have structure which follow a set of internal rules.

To counter empiricism, Chomsky proposes the rationalist notion of a universal grammar (UG), which all speakers are born with. A speaker's UG is a set of constraints which must be specialised for the particular language the speaker acquires, using the particular performance data they're exposed to.

Interestingly, when Katz and Fodor (1963) port Chomsky's ideas to semantics, they don't actually commit to a story about how acquisition happens: “(by conditioning? by the exploitation of innate mechanisms? by some combination of innate endowment and learning?)”(ft 3, p172). But they will later make separate claims. On the one hand, Katz and Chomsky (1975) argue that both empiricists and rationalists need innateness, albeit in different ways. For empiricists, it is (merely) ‘a machinery for instituting associative bonds’; for rationalists, on the other hand, it imposes ‘severe restrictions on what a simple idea can be and on what ways simple ideas can combine’. On the other hand, Fodor himself will end up being the representative of an extreme stance on innateness and concepts, claiming in The Language of Thought (1975) that all lexical concepts are innate and are simply ‘triggered’ by performance data.

Being interested in innateness means caring about what is common to all members of the human species. By definition, it means caring about types and regularities, about the knowledge and rules we are endowed with. It should then be natural to claim, as Chomsky does, that one's object of study is competence (the innate set of rules that explains human linguistic commonalities) rather than performance (the messy, idiosyncratic use of those rules in human behaviour). It should be just as natural to limit one's approach to productivity (and thus to compositionality) to the combination of grammatical types (whether syntactic or lexical). And it is entirely reasonable to be somewhat suspicious of the next type of semantics we’ll introduce. A semantics that encodes worlds, things and sets of things that mysteriously seem to live outside of the subject…

Montague. Natural languages are formal languages

In her account of the origins of formal semantics, Partee (2011) points out that the problem with the Chomskian theory of grammar, and by extent, with Katz and Fodor's approach to semantics, is that it gets into trouble when encountering quantifiers. The sentence Every candidate voted for every candidate is not semantically equivalent to Every candidate voted for him/herself. That is however what Chomskian transformational grammar would predict. Something seems to be missing, and this will spark a different approach to semantics.

Enters Montague. Like Katz and Fodor, Montague believes in a homomorphism between syntax and semantics, but in his framework, this homomorphism is implemented in logic, prompting the famous claim:

“I reject the contention that an important theoretical difference exists between formal and natural languages.” (Montague, 1970)

Inspired by the work of Alfred Tarski, Montague contends that sentences and their constituents are in a relation of correspondence with 'worlds' or 'state-of-affairs', and that this correspondence relation can be expressed using an intensional logic. In a Montagovian approach, sentences have truth values (‘A dog sleeps’ is true or false with respect to a world) and parts of sentences have extensions (‘A dog’ in ‘A dog sleeps’ might refer to Lassie in that same world). Composition at the syntactic level is clearly reflected in the parts of the world that are picked out in the semantics. Sleeping dogs are, in the simplest possible setup, the intersection of some set of dogs and some set of sleeping things, in an entirely bottom-up fashion. Having access to sets of entities makes the proper treatment of quantifiers a reality: if some dogs sleep, the set of dogs partially overlaps with the set of sleeping things. If all dogs sleep, the set of dogs is contained in the set of sleepers.

Let's now contrast this view with the Katz and Fodor framework, remembering the tenets of the Chomskian approach: a) a linguistic theory should tell us which sentences are felicitous in a certain language; b) contextual effects should be kept outside the theory; c) language is in the mind.

a) Linguistic felicity: Montagovian semantics has an important feature, noted by Partee (2011): “semantics itself is in the first instance concerned with truth-conditions (not actual truth, as is sometimes mistakenly asserted)”. That is, truth does not have anything to do with the real world. Whoever wants ideas to sleep (furiously or not) can intersect the set of ideas and the set of sleeping things. To a Chomskian’s horror, acceptability is of no concern to the logician.

Faced with two antithetical positions, it is worth asking whether in fact, semantic felicity is a reality. In his study of concept combination, Hampton (1991) indicates this might not be the case. In his experiment, he asks human subjects to try to imagine a fish that is a also a vehicle. His results emphasise the creativity exhibited by people when asked that question: “Some subjects put a saddle on the back of the fish [...] while still others surgically implanted a pressurized compartment within the fish.” In other words, when making sense of unattested combinations, people are able to generate the possible world that would make the sentence true / the extension non-empty. If required, that world can be very far from reality. This is hard to fit with a story of selectional constraint à la Katz and Fodor. Montague’s semantics, on the other hand, naturally avoids the issue by positing an infinity of possible worlds, with sentences being true in a set of worlds and constituents having intensions that map worlds to extensions following the principle of compositionality. Infinity, of course, does not ensure that there is a world with fish implanted with pressurized compartments, but in principle, at least, nothing precludes it.

b) Context: As a philosopher, Montague is very aware of the ubiquity of context in language, exemplified in phenomena like tense, modality and propositional attitudes. He treats the issue in a 1970 essay on pragmatics, but in a way that carefully avoids the 'principle of contextuality' and leaves the account cleanly bottom-up. In that essay, he introduces contexts of use: who utters the sentence, where and when; the state of the world; the surrounding discourse, etc. Context is formalised as finite tuple of indexicals, where intensions are functions from indices to extensions.

Adhering to purely bottom-up compositionality does make for a somewhat cumbersome semantics, though. Hobbs and Rosenschein (1978) give the following summary of Montague semantics (accompanied by the tongue-in-cheek footnote: “This sentence parses unambiguously.”)

“[the reader of Montague] finds that English sentences are supposed to acquire meaning by being mapped into a universe of possible worlds, of infinite sets and functionals of functions on these sets. He finds, for example, the word ‘be’ defined as a functional mapping a function from possible worlds and points in time into entities and a function from possible worlds and points in time into functionals from functions from possible worlds and points in time into functionals from functions from possible worlds and points in time into entities into truth values into truth values into truth values.”

There is more to this quote than a humorous insight into the complexity of formal semantics. It brings to light what the semantics is made of – worlds, sets, functions – and inevitably questions the cognitive status of the framework.

c) Language is in the mind: It should be clear from the definition above that the Montagovian account is not a cognitively informed one: it is doubtful that a speaker should hold an infinity of possible worlds, or sets, or anything else in their mind. The theory also lacks some acquisition story which would explain where, in the first place, those worlds and sets should come from, and how they might emerge in children, and evolve in adults.

But perhaps more fundamentally, language in Montague semantics is an interpreted formal system, that is, a system which does truth values and reference, and it is unclear how to reconciling this aspect of the theory with the psychological notion of competence cherished by Chomskians. In a 1979 article, Partee asks whether a competent speaker – one who can deal with the productivity of language – is an individual who always knows the extension of any new linguistic constituent. For instance, let's assume a speaker who hears that Class A stars have a temperature between 7,500 and 10,000 K. Does it mean that they would necessarily be able to point at them in the night sky? They may understand a lot of the semantics of that sentence, and be none the wiser as regards the extension of class A stars. Are they still competent then? And what does it mean for matters of acquisition, in settings where a child might be hearing many new words every day, without ever being certain about the corresponding referents?

The question of bringing together formal semantics and cognitive science remains unsolved. In her contribution at the 9th Annual Joshua and Verona Whatmough Lecture, Harvard (2014), Partee gives an account of the philosophical issues surrounding the question, eventually compromising and concluding that truth theory may have to live with imperfect truth if it is to reside in the mind.

So in the same way that Chomsky’s focus on innateness leads him to carefully avoid the messier parts of semantics in his account of productivity, Montague’s claim about the model-theoretic nature of language commits him to a particular treatment of knowledge and beliefs which does not play well with the conceptual aspects of composition. It has nothing to say about innateness (where do those worlds come from?) and struggles with aspects of semantic acquisition.

So let us step back and follow another route out of Chomskian linguistics.

Fillmore. Language is inseparable from context.

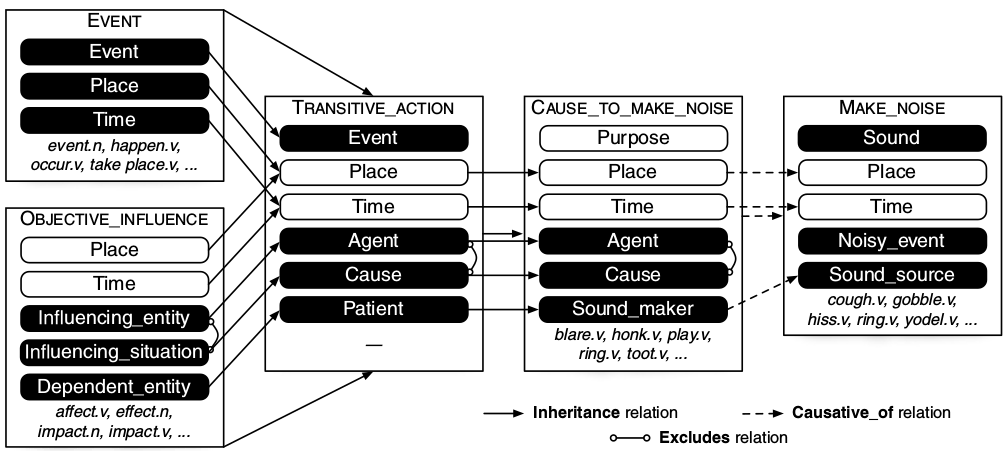

Fillmore is initially involved in syntactic work in the spirit of Chomskian transformational grammar (1982). He develops a ‘case grammar’ to encode selectional restrictions and Katz and Fodor’s projection rules. This approach to grammar will famously become frame semantics.

For Fillmore, a frame is a conceptual representation of a situation. He writes: “I thought of each case frame as characterizing a small abstract ‘scene’ or ‘situation’, so that to understand the semantic structure of the verb it was necessary to understand the properties of such schematized scenes.” Thus, a frame can be something as simple as the encoding of a verb’s argument structure, or as complex as the description of an entire script, such as a going-to-the-restaurant or a taking-the-bus situation.

Fillmore’s interest is in explaining why a speaker chose the specific words they uttered. He formalises this idea in the notion of U-semantics (semantics of understanding). His semantics is perhaps the first to try and explicitly encode the paradox of the two principles of compositionality:

The U-semantics account is compositional in that its operation depends on knowledge of the meanings of individual lexical items [...], but it is also 'non-compositional' in that the construction process is not guided by purely symbolic operations from bottom to top. (Fillmore, 1985)

In terms of fundamental assumptions, if we wish to contrast U-semantics with the other approaches we have looked at, we will find that Fillmore distinguish himself by making as few assumptions as possible. His paper on the ‘Semantics of Understanding’ opens with the following disclaimer:

“A U-semantic theory takes as its assignment that of providing a general account of the relation between linguistic texts, the contexts in which they are instanced, and the process and products of their interpretation. Importantly, such a theory does not begin with a body of assumptions about the difference between (1) aspects of the interpretation process which belong to linguistics proper and (2) whatever might belong to co-operating theories of speaking and reasoning and speakers’ belief systems.”

So Fillmore is at the opposite end of Chomsky when it comes to setting boundaries to the study of language. Semantics and pragmatics, according to him, cannot be ignored. And there is no prevalence of syntax over the other layers of language: semantics, for instance, can influence syntax. This is a huge shift with regard to setting the scope of linguistics.

In spite of being very unconstrained, Fillmore's approach can nevertheless be looked at again from the point of view of the three aspects we have looked at previously, (felicity, context, relation to cognition). This time, we will start with the theory's relation to psychological aspects of language.

a) Language is in the mind: Frame semantics is a cognitive account of language which relates grammar to a process of conceptualisation. Parsing a sentence means retrieving the (conceptual) frames that individual words evoke, and relating them in a way that matches the semantics of the utterance. For instance, the sentence The dog sleeps may evoke a DOG and a SLEEP frames, and DOG will fill the agent role of SLEEP. By virtue of activating and associating conceptual content, the framework is fundamentally cognitive. In contrast to Chomskian linguistics, though, it does not make strong assumptions about which parts of language are inbuilt in human cognition. Fillmore (1985, p.232) simply acknowledges that some frames might be innate and others acquired.

b) Context: If Fillmore is concerned about context, it is notable that he approaches the question in a radically different way from Montague. Fillmore's idea of a U-semantics is in fact in clear contradiction with truth-theoretic semantics (T-semantics). His argument is that frequently, speakers find it difficult to give a truth value to a given sentence while they may not have any problem giving the same sentence an interpretation. He gives the example of a situation where some children are playing inside an abandoned bus in a junkyard. In that condition, he asks, is the sentence ‘The children are on the bus’ true or false? People find it extremely difficult to make a categorical judgement on this. They however straightforwardly report that they would find ‘The children are IN the bus’ more appropriate for the situation, given that the bus is not anymore operational. So, the claim goes, context clearly influences the choice of words describing a situation, but independently from a speaker's ability to emit truth values.

c) Linguistic felicity: By taking a strong stance on model theory, and therefore shunning possible worlds, frame semantics however reduces the scope of productivity back to some kind of selectional preference, just as in the Katz and Fodor model. It certainly is a different type of selectional preference: one that emerges from knowledge of entire scripts, one that breaks the boundaries between syntax, semantics and pragmatics. But the proposed semantics is very much in the spirit of a grammar encoding types. And this is a problem for any kind of composition that requires fine-grained, ad-hoc manipulation of concepts. Surgically implanting a pressurized compartment inside a fish when hearing the string fish vehicle seems to involve many more possible and impossible Montagovian worlds than a polite restaurant script. So by committing to meaning being encoded in the lexicon, inside some kind of grammar, Fillmore subscribes to a compositionality based on rules and regularities (as exemplified by constructionist approaches). Hampton’s subjects’ creativity, however, indicates that meaning may go well beyond rules.

For a theory of compositionalities

So in the end, it may be misguided to talk of Compositionality (with capital C) as the mechanism of productivity. We should perhaps rather talk of compositionalities, and how each one contributes to one aspect of the new.

Clearly, a complete theory of productivity will have to find interaction patterns between those different composition mechanisms. Montague's belief in the homomorphism between syntax and semantics was a step in that direction. So was Fillmore's intuition that contextual regularities could be encapsulated in a grammar. But while these approaches reuse notions and tools from other theories, they only partly integrate their research questions.

When considering a phenomenon as fundamental as productivity, losing a research question necessarily introduces holes and paradoxes in the theory. This may not necessarily be a bad thing. After all, explaining linguistic topology, or language acquisition, or reference processes, is in itself a hard enough task. And done right, it can in fact solve more problems than it creates. The bottom-up vs top-down paradox, for instance, disappears as soon as one properly delimits one's object of study. One can blame Chomskian linguistics or Montagovian semantics for being narrow (how could one possibly ignore meaning? how could one be so stuck on logic?) But they do have the advantage of being consistent with respect to their underlying research question. There are other good examples of doing this in the recent literature. For instance, Bender et al (2015) explicitly addresses the compositionality vs context paradox in relation to parsing, ending up with a working definition of the phenomenon that correctly ignores top-down effects.

At the same time, if productivity itself is the goal, a grand theory would surely benefit from integrating the constraints and freedoms of linguistic competence. How can meaning be in the mind and about the world (or worlds)? How can language be about regularities and expectations, but also about breaking rules? How do we construct the meaning of fish in the process of language acquisition, just to deconstruct it as easily and make it a submarine in the context of vehicle? Such questions may or may not be about compositionality. Even if they are, they may require compositionalities held together by some higher principle.

Many people in the AI community are thinking about compositionality right now. There is a sense that the concept is intrinsically related to the ability of machine to truly generalise beyond their training data. That it is key to growing complexity from a basic set of skills. That it touches on fundamental questions about natural (and artificial) creativity. The lack of a proper grasp on the concept may seem frustrating. Taking a more historical perspective on the issue, however, reveals that many pieces of the puzzle are already there, and that they lie not in ‘compositionalities’ themselves (there are many of them), but in the theoretical constraints that made them what they are. And it is perhaps those constraints, rather than compositionality itself, that we should worry about. The definition of compositionality interacts with our notions of syntax and pragmatics, with our working definitions of meaning and worlds, and even with epistemological questions about linguistics (do we care about the mind?). If we want to get ahead on the topic, we must look deeper into the foundations of each approach.

-------

Aurelie Herbelot is an assistant professor at the Center for Mind/Brain Sciences, University of Trento (Italy). Her research is situated at the junction of computational semantics, cognitive science and AI. She leads the Computational Approaches to Language and Meaning (CALM) group, focusing on investigating the link between language and worlds (the real world and others). She is particularly interested in models of semantics that bridge across formal and distributional representations of meaning.

Citation

For attribution in academic contexts or books, please cite this work as

Aurelie Herbelot, "How to Stop Worrying About Compositionality", The Gradient, 2020.

BibTeX citation:

@article{herbelot2020how,

author = {Herbelot, Aurelie},

title = {How to Stop Worrying About Compositionality},

journal = {The Gradient},

year = {2020},

howpublished = {\url{https://thegradient.pub/how-to-stop-worrying-about-compositionality-2 } },

}

If you enjoyed this piece and want to hear more, subscribe to the Gradient and follow us on Twitter.

References

Bender, E. M., Flickinger, D., Oepen, S., Packard, W., & Copestake, A. (2015). Layers of interpretation: On grammar and compositionality. In Proceedings of the 11th international conference on Computational Semantics, IWCS 2015, (pp. 239-249).

Chomsky, N. 1967. A Review of B. F. Skinner’s Verbal Behavior. In Leon A. Jakobovits and Murray S. Miron (eds.), Readings in the Psychology of Language, Prentice-Hall, 1967, pp. 142-143.

Cresswell, M. (1973). Logics and Languages, London: Methuen.

Das, D., Chen, D., Martins, A.F., Schneider, N. and Smith, N.A. (2014). Frame-semantic parsing. Computational linguistics, 40(1), pp.9-56.

Fillmore, C. J. (1982). Frame semantics. In ‘Linguistics in the Morning Calm’, Linguistic Society of Korea (ed.), 111–137. Seoul: Hanshin Publishing Company. Reprinted ‘Cognitive linguistics: Basic readings’ (2008), 34, 373-400.

Fillmore, C. J. (1985). Frames and the semantics of understanding. Quaderni di semantica, 6(2), 222-254.

Fodor, J. and LePore, E. (1992). Holism: A Shopper’s Guide, Oxford: Blackwell.

Hampton, J. A. (1991). The combination of prototype concepts. In ‘The psychology of word meanings’, ed. P. Schwanenflugel, 91-116. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Katz, J. J., & Fodor, J. A. (1963). The structure of a semantic theory. Language, 39(2), 170-210.

Montague, R. (1970a). Pragmatics and intensional logic. Synthese, 22(1-2), 68-94.

Montague, R. (1970b). English as a Formal Language. In Bruno Visentini (ed.), Linguaggi nella societa e nella tecnica. Edizioni di Communita. pp. 188-221.

Partee, B. (1979). Semantics—mathematics or psychology? In ‘Semantics from different points of view’ (pp. 1-14). Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg.

Partee, B. (1984). Compositionality. Reprinted in ‘Compositionality in formal semantics: Selected papers’, 2008. John Wiley & Sons.

Partee, B. (2011). Formal semantics: Origins, issues, early impact. Baltic International Yearbook of Cognition, Logic and Communication, 6(1), 13.

Partee, B. (2014). The History of Formal Semantics: Changing Notions of Linguistic Competence. Harvard, 9th Annual Joshua and Verona Whatmough Lecture, April 28, 2014.

Pelletier, F. J. (2001). Did Frege believe Frege’s principle?. Journal of Logic, Language and information, 10(1), 87-114.