In this post I will attempt to summarize some elements of the recent discussion that happened among AI researchers as a result of bias found in the model associated with the paper "PULSE: Self-Supervised Photo Upsampling via Latent Space Exploration of Generative Models". I will also offer my personal reflection on this discussion and on what can be learned from it with regards to the technical topic of bias in machine learning, best practices for AI research, and best practices for discussing such topics. I write this because I believe they are valuable lessons that are worth noting. Some of these lessons are more subjective than others, so I hope that even if you disagree with the perspective offered here you will still consider it.

Table of Contents

On the Value of Demos

It started with a Tweet announcing a Colab notebook containing a demo of the work presented in the recent paper "PULSE: Self-Supervised Photo Upsampling via Latent Space Exploration of Generative Models":

Face Depixelizer

— Bomze (@tg_bomze) June 19, 2020

Given a low-resolution input image, model generates high-resolution images that are perceptually realistic and downscale correctly.

😺GitHub: https://t.co/0WBxkyWkiK

📙Colab: https://t.co/q9SIm4ha5p

P.S. Colab is based on thehttps://t.co/fvEvXKvWk2 pic.twitter.com/lplP75yLha

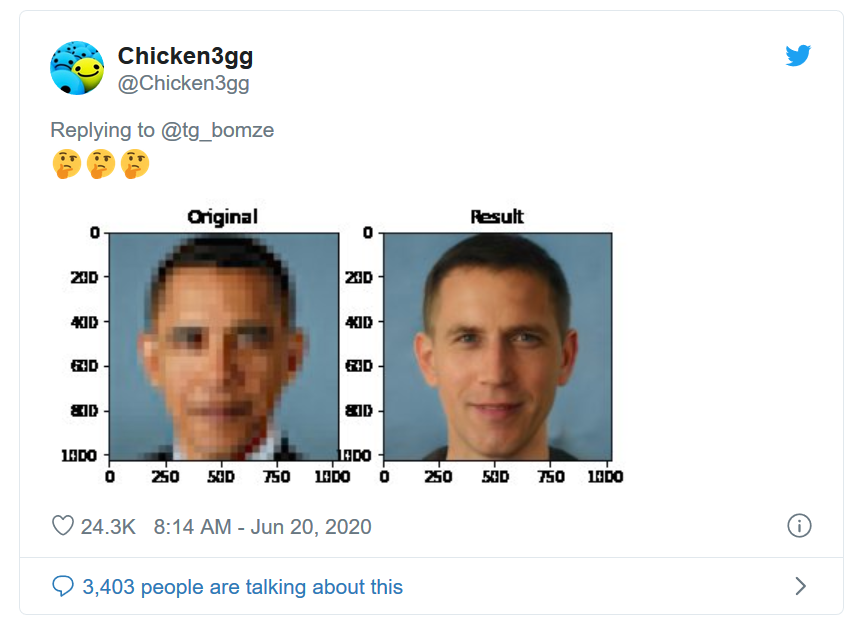

This was soon responded to with a demonstration that the method appears to be biased in favor of outputting images of white people, with a concrete example of a pixelated image of Barack Obama:

🤔🤔🤔 pic.twitter.com/LG2cimkCFm

— Chicken3gg (@Chicken3gg) June 20, 2020

The reaction to this bias, and the discussion concerning it, was loud enough that it was covered in the popular press with The Verge's "What a machine learning tool that turns Obama white can (and can’t) tell us about AI bias". While seeing yet another example of problematic bias in AI was not pleasant for anyone, I still think it’s good insofar as it did not simply go unnoticed and the conversation was had, so:

Lesson 1: interactive demos are useful to have in addition to plain source code, as they can allow people to easily interact with the model and potentially point out issues with it.

On Best Practices for Addressing Bias in AI Models

In response, the authors of the paper (Sachit Menon*, Alexandru Damian*, Shijia Hu, Nikhil Ravi, Cynthia Rudin) added a comment on the project GitHub repo:

The new section in the paper addresses the issue directly:

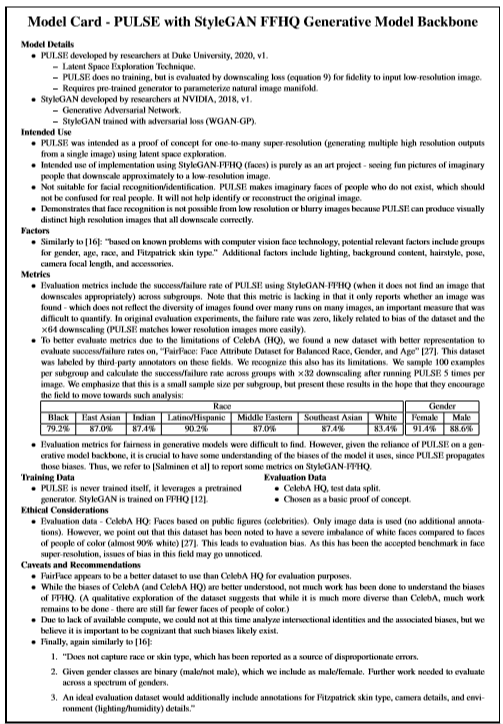

As does the model card in the appendix:

This, in my opinion, was a well done response by the authors. Sections addressing limitations or ethical concerns with the research and the idea of model cards are both existing ideas advocated by researchers focused on the ethics of AI. In fact, the paper introducing the idea of model cards had an example of a model card for a smile detection model with very similar caveats as are found in this paper:

Therefore we can conclude:

Lesson 2: there exist recommended best practices for addressing potential bias in applied AI research, and the idea of model cards is particularly relevant.

On the Source of Bias in Machine Learning Systems

Meanwhile, the conversation around this topic on Twitter further took off based on a tweet by Dr. Yann LeCun that offered an explanation on why the bias in the model existed:

ML systems are biased when data is biased.

— Yann LeCun (@ylecun) June 21, 2020

This face upsampling system makes everyone look white because the network was pretrained on FlickFaceHQ, which mainly contains white people pics.

Train the *exact* same system on a dataset from Senegal, and everyone will look African. https://t.co/jKbPyWYu4N

In response, Dr. Timnit Gebru, a leading researcher on fairness, accountability, and transparency in AI, noted that the idea that bias in ML systems comes only from data is incorrect:

Even amidst of world wide protests people don’t hear our voices and try to learn from us, they assume they’re experts in everything. Let us lead her and you follow. Just listen. And learn from scholars like @ruha9. We even brought her to your house, your conference.

— Timnit Gebru (@timnitGebru) June 21, 2020

She also noted the recent Tutorial on Fairness Accountability Transparency and Ethics in Computer Vision at CVPR 2020 as an educational resource to better understand this topic:

Yann, I suggest you watch me and Emily’s tutorial or a number of scholars who are experts in this are. You can’t just reduce harms to dataset bias. For once listen to us people from marginalized communities and what we tell you. If not now during worldwide protests not sure when.

— Timnit Gebru (@timnitGebru) June 21, 2020

Other AI researchers also replied with commentary on this:

I’m by no means an expert on ML bias+fairness and I think it’s one of the most challenging research areas.

— hardmaru (@hardmaru) June 21, 2020

But whenever I can, I try to listen to what people working in this area are saying, and try to understand some of the nuances to expand my worldview.https://t.co/emRJiNfjXS https://t.co/ajLaQw7Ert

I am confused by this discussion. Surely we are all coming into this knowing that learning algorithms (not to mention complicated *systems* that involve multiple steps, parameters, loss functions, etc) have inductive biases going beyond the “biases” in data, right? https://t.co/e207Ku1y5N

— Charles Isbell (@isbellHFh) June 22, 2020

ML system are biased when data is biased. sure.

— (((ل()(ل() 'yoav)))) (@yoavgo) June 21, 2020

BUT some other ML systems are biased regardless of data.

AND creating a 100% non-biased dataset is practically impossible.

AND it was shown many times that if the data has little bias, systems *amplify it* and become more biased. https://t.co/dhxC7aJe95

Train it on the *WHOLE* American population with:

— #BlackLivesMatter El Mahdi El Mhamdi (@L_badikho) June 21, 2020

1) an L2 loss (average error), and almost everyone will look white.

2) an L1 loss (median error), and more people might look black.

stop pretending that bias does not also come from algorithmic choices.https://t.co/WH2MxIGxdX

A particularly relevant reply also pointed out the paper "Predictive Biases in Natural Language Processing Models:A Conceptual Framework and Overview" and noted that "we just published a study of the most common sources of bias in NLP systems, and data is only one of them":

We just published a study of the most common sources of bias in NLP systems, and data is only one of them.https://t.co/QcVlD0arUT

— Dirk Hovy (@dirk_hovy) June 22, 2020

One of the more overlooked sources is our own design and thinking about the process:https://t.co/qsapQ0NmyR

Dr. LeCun responded to these points by clarifying he more specifically meant that data is the primary source of bias in most modern ML systems and that addressing issues in the data is the best way to approach such problems:

7 years ago, most ML systems used hand-crafted features, which are a primary cause of bias.

— Yann LeCun (@ylecun) June 22, 2020

But nowadays, people use generic DL architectures fed with raw inputs, greatly reducing bias from feature and architecture design.

This leaves us with data as the primary source of bias.

I was not talking about ML theory-style inductive bias (which is data independent).

— Yann LeCun (@ylecun) June 22, 2020

I was talking about garden variety everyday bias in ML systems, which is either in the features or in the data.

But if features are learned, as in DL, isn't bias largely in the data?

The most efficient way to do it though is to equalize the frequencies of categories of samples during training.

— Yann LeCun (@ylecun) June 21, 2020

This forces the network to pay attention to all the relevant features for all the sample categories.

Which was met with skepticism:

Indeed. This is a bold assertion that needs proof. The emerging take on learning is that it's an interaction of architecture, data, training algorithm, loss function, etc., but somehow this perspective goes out the window when we talk about bias? You can't have it both ways.

— Maxim Raginsky (@mraginsky) June 22, 2020

But that's also an algorithmic choice.

— alex rubinsteyn (@iskander) June 22, 2020

I don't think that "data" and "algorithm" are easily separable here -- algorithmic choices are (or should be) guided by properties of the data and their social consequences.

Have you considered that the bias is "largely" in the researchers, not in the tools?

— ricardo prada, phd (@eldrprada) June 22, 2020

Fixing data is a facile answer. There were dozens of decisions between the idea and publication that could have produced a better outcome, but the researchers never considered them important.

A problem with this framing is that it moves responsibility away from the designer of an algorithm to think about unsurfaced assumptions in the design of an algorithm. That alone means it is harder for the “engineer” to even understand the implications of later decisions.

— Charles Isbell (@isbellHFh) June 22, 2020

Dr. LeCun generally responded by reasserting his position:

Sure.

— Yann LeCun (@ylecun) June 22, 2020

But choosing between logistic reg, fully-connected net, or ConvNet working from pixels, will not cause the system to be intrinsically biased towards people of certain types.

Now, the moment you hand-design features, you introduce bias.

And the data can obviously be biased.

And further scrutiny of this stance followed:

So, it's a feature that we have ML algorithms that learn their own features and so (let's say) might minimize designer bias...

— Charles Isbell (@isbellHFh) June 24, 2020

...but that's also a bug: it means the mechanism for encoding domain knowledge is finding perfect data.

Is that an optimal, *ahem*, design choice?

Could the algorithms be adjusted to be less racially biased? YES! Could the data be adjusted to contain less racial bias? YES! It is a *dumb* argument because BOTH THINGS ARE SOLUTIONS. Can we talk about how tech can do better now?

— 🔥Kareem Carr🔥 (@kareem_carr) June 23, 2020

This is a common behavior when people are confronted with the idea that a culture they care about and are involved in is racist. It moves the discussion from an uncomfortable conversation about racial bias to a more comfortable one about technical details.

— 🔥Kareem Carr🔥 (@kareem_carr) June 23, 2020

Further discussion on the subject also occurred on reddit in the thread "[Discussion] about data bias vs inductive bias in machine learning sparked by the PULSE paper/demo". While people are still split on the conclusions to be drawn from this discussion and finer points that arose from it, at a high level at least this lesson can be drawn:

Lesson 3: data can be a source of bias in Machine Learning systems, but is not the only source, and the harms potentially caused by such systems can result from more than just flawed datasets.

On Etiquette For Public Debates

In reply to Dr. Gebru, Dr. LeCun responded by clarifying he didn’t mean that data is the only source of bias, and offered his thoughts on the sources of bias in AI in a Twitter thread:

If I had wanted to "reduce harms caused by ML to dataset bias", I would have said "ML systems are biased *only* when data is biased".

— Yann LeCun (@ylecun) June 22, 2020

But I'm absolutely *not* making that reduction.

1/N

There are many causes for *societal* bias in ML systems

— Yann LeCun (@ylecun) June 22, 2020

(not talking about the more general inductive bias here).

1. the data, how it's collected and formatted.

2. the features, how they are designed

3. the architecture of the model

4. the objective function

5. how it's deployed

Now, if you use someone else's pre-trained model as a feature extractor, your features will contain the biases of that system (as @soumithchintala correctly pointed out in a comment to my tweet).

— Yann LeCun (@ylecun) June 22, 2020

5/N

He concluded this thread by calling for discussion to happen in a non-emotional way and for others to not assume bad intent from other people:

It's also important to avoid assuming bad intent from your interlocutor.

— Yann LeCun (@ylecun) June 22, 2020

It only serves to inflame emotions, to hurt people who could be helpful, to mask the real issues, to delay the development of meaningful solutions, and to delay meaningful action.

17/N

N=17.

To which Dr. Gebru responded by disengaging:

Maybe your colleagues will try to educate you. Maybe not. But I have better things to do than this.

— Timnit Gebru (@timnitGebru) June 22, 2020

And Dr. LeCun responded as follows:

I'm sad that you are not willing to discuss the substance.

— Yann LeCun (@ylecun) June 22, 2020

I had hoped to learn something from this interaction.

There are several groups at FB that are entirely focused on fairness, bias and social impact of ML/AI.

There are many FAIR projects on this too (I cited only one).

Some criticized the thread from Dr. LeCun and characterized it as lecturing Dr. Gebru on her subject of expertise, as being condescending, and as involving Tone-Policing:

She IS the expert we all look up at. Not you, I'm sorry if that hurts you. I'm glad you took the time to engage, but you decided to take a position that is not rightfully yours. You can LEARN a lot from Timnit (and many others), if you open up to it. 2/2

— gvdr (@ipnosimmia) June 22, 2020

You gave a tweetorial to an expert in this field and neither refuted nor asked for clarification on ANY of her points.

— Devin Guillory (@databoydg) June 22, 2020

How do you expect her to engage? You presented the bare minimum of substance which you had read ANY of the literature would be obvious.

@ylecun perhaps she is unwilling because you did not 'discuss' or engage-you gave a 17-tweet lecture which asked her not one question and ended with telling her, a Black woman scholar, to fix her tone and control her emotions. You are far too smart not to know what that means.

— Shannon Vallor (@ShannonVallor) June 23, 2020

I'm confident you could learn a bit more auto-didactically before coming to this discussion and asking a WOC to teach you.

— johnurbanik (@johnurbanik) June 22, 2020

Next time you wish to learn from a marginalized person, you could show empathy and avoid tone policing and condescension. We all could grow in this respect.

You clearly did not hope to learn anything from this interaction as you were literally explaining to a fellow ML expert what imbalanced data is, as if they wouldn't already know. You don't respect people who disagree with you and you most certainly don't want to learn from them.

— Jonathan Peck (@ArcusCoTangens) June 23, 2020

You should have stopped at 2. People ask you to listen and you proceed to explain the issue back at them.

— Victor Zimmermann (@VictorAndStuff) June 23, 2020

In partial response to this criticism, Dr. LeCun said the thread was “obviously not just for Timnit”, and acknowledged her expertise in this subject:

Did you just label scientific discourse as "mansplaining"?

— Habib Slim (@HabibSlim3) June 22, 2020

The thread was obviously not just for Timnit, but for the people who read this exchange and who are not nearly as knowledgeable about these issues as she is.

— Yann LeCun (@ylecun) June 22, 2020

I learn things about topics I'm an expert in from pple with much less experience than me, like my students and postdocs.

Which was met with this criticism:

While you might have intended the thread for everyone, that's not ''obvious''. Your explanations are a reply to her tweet saying "listen to us", but you don't credit them, and you say that we shouldn't be emotional about these questions (obviously, referring to Timnit's tweet).

— Ana Marasović (@anmarasovic) June 23, 2020

Others defended Dr. LeCun:

Accusative comments like these only help to divide people.

— David van Niekerk (@DavidPetrus94) June 23, 2020

You immediately accused someone that posted a constructive and polite comment of 'mansplaining'. Ironically if there's anyone that is an expert in bias in ML it is Turing Award winner @ylecun.

Damn Yann, sorry for what's happening. People are totally mischaracterizing what you are saying. I guess they are indeed angry given the situation, but you just got caught in the crossfire. Overall, I agree with you, but even if I didn't it's clear you are engaging in good faith.

— Rafael (@sohakes) June 23, 2020

I salute @ylecun for your calmness and patience to clarify and explain the matter with reasons.

— Chunnan Hsu (@ChunNanHsu) June 22, 2020

You have been chosen by the popular mob. Now there is nothing you can do but apologise for something you haven't done.

— Kaelan (@KaelanDon) June 22, 2020

This was largely also the stance of the YouTube video "[Drama] Yann LeCun against Twitter on Dataset Bias", and some comments in response to it, such as this one:

"We need more people like Yann defending their rational positions against ignorant mobs in public so we can be inspired to think for ourselves! Yann's contributions to humanity are immeasurable, if only the people jumping to attacks realized the pettyness of their actions..."

Further discussion of Dr. LeCun's response to Dr. Gebru followed:

First, when someone gives you feedback, resist the urge to defend / explain yourself. See this explanation by @mekkaokereke : https://t.co/Hz4uyYHSIO

— Nicolas Le Roux (@le_roux_nicolas) June 23, 2020

Note that this is true "even when the criticism is unfounded".

Fifth, you asked to not be emotional, which is tone policing (https://t.co/StDExC6x3S), again known to maintain the balance of power. This also goes hand-in-hand with stereotypes about Black women (https://t.co/bw8ysYilt3)

— Nicolas Le Roux (@le_roux_nicolas) June 23, 2020

For those asking what is missing from Yann's original, very narrow framing of bias:https://t.co/4AxGfh2NiP

— Rachel Thomas (@math_rachel) June 23, 2020

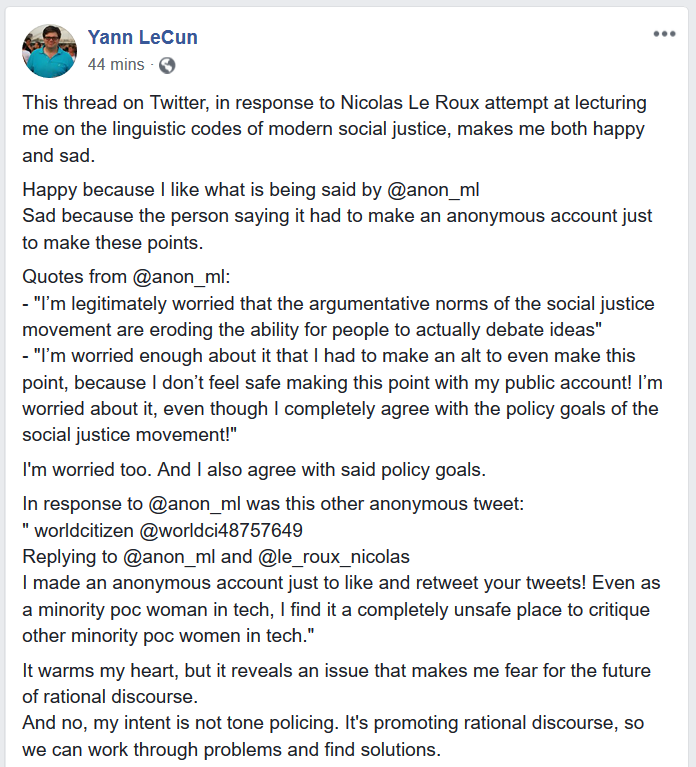

Which led to responses that characterized Dr. LeCun's response as just an attempt at rational debate and dismissed the criticisms regarding Tone-Policing and Mansplaining as "social justice critique":

But this isn’t how reasoned debate works! This isn’t how actually convincing people of anything happens! I’m legitimately worried that the argumentative norms of the social justice movement are eroding the ability for people to actually debate ideas

— anon_tech_ML (@anon_ml) June 24, 2020

Which Dr. LeCun endorsed:

Dr. LeCun issued this statement soon after that:

I really wish you could have a discussion with me and others from Facebook AI about how we can work together to fight bias.

— Yann LeCun (@ylecun) June 26, 2020

The PULSE model and this exchange were later covered in VentureBeat with the article "A deep learning pioneer’s teachable moment on AI bias".

Regardless of which stance you agree with, it makes sense to at least understand the criticisms directed at Dr. LeCun. From Racism 101: Tone Policing:

“Tone policing describes a diversionary tactic used when a person purposely turns away from the message behind her interlocutor’s argument in order to focus solely on the delivery of it.

...

Here’s a good rule of thumb: when you are out of line, you don’t get to set the conditions in which a conversation can occur. That’s privilege at play. You need to truly listen to how and where you went wrong, and then do better in future.”

Regarding the criticisms of Dr. LeCun explaining the topic to Dr. Gebru despite her being an expert on it, it is worth knowing The Psychology of Mansplaining:

According to the Oxford English Dictionary editors, mansplaining is “to explain something to someone, typically a man to woman, in a manner regarded as condescending or patronizing” (Steinmetz, 2014). The American Dialect Society defines it as “when a man condescendingly explains something to female listeners” (Zimmer, 2013). Lily Rothman, in her “Cultural History of Mansplaining,” elaborates it as "explaining without regard to the fact that the explainee knows more than the explainer, often done by a man to a woman.”

Mansplaining as a portmanteau may be new, but the behavior has been around for centuries (Rothman, 2012). The scholarly literature has long documented gendered power differences in verbal interaction: Men are more likely to interrupt, particularly in an intrusive manner (Anderson and Leaper, 1998). Compared to men, women are more likely to be interrupted, both by men and by other women (Hancock and Rubin, 2015). Perhaps, in part, because they are accustomed to it, women also respond more amenably to interruption than men do, being more likely to smile, nod, agree, laugh, or otherwise facilitate the conversation (Farley, 2010).

...

Mansplaining is problematic because the behavior itself reinforces gender inequality. When a man explains something to a woman in a patronizing or condescending way, he reinforces gender stereotypes about women’s presumed lesser knowledge and intellectual ability.

This is especially true when the woman is, in fact, more knowledgeable on the subject.

Related to this is The Universal Phenomenon of Men Interrupting Women:

“Victoria L. Brescoll, associate professor of organizational behavior at the Yale School of Management, published a paper in 2012 showing that men with power talked more in the Senate, which was not the case for women. Another study, “Can an Angry Woman Get Ahead?” concluded that men who became angry were rewarded, but that angry women were seen as incompetent and unworthy of power in the workplace.“

To be clear, I am not claiming Dr. LeCun intended any disrespect in how he communicated or otherwise attributing any negative intent to him, but rather am explaining the criticisms of his response.

I have phrased the above as objectively as I could, because I really do want people uncomfortable with the criticism directed at Dr. LeCun to at least consider and try to understand it better. Some may question whether it's worth it to consider this exchange at such length, but research is a community endeavour, and norms of communication within the community therefore naturally matter. I will contain my personal perspective on this exchange to the following optional section, in case it may further help people consider these criticisms:

Further discussion of this exchange, from my perspective

I do think Dr. LeCun's response to Dr. Gebru deserves the scrutiny it received. From my perspective, this is a fair summary:

-

Dr. LeCun tweets that “ML systems are biased when data is biased.” This can be interpreted in multiple ways, with one interpretation being that data is the only factor that matters, and another being that data is the main problem in this particular case.

-

Dr. Gebru replies in an exasperated way noting that the first possible interpretation is incorrect and that experts such as her say this often. Implicitly, it's clear that this exasperation must be partially because this is a common and harmful misconception experts such as Dr. Gebru have to fight against.

-

Dr. LeCun responds with

“If I had wanted to 'reduce harms caused by ML to dataset bias', I would have said "ML systems are biased only when data is biased". But I'm absolutely not making that reduction. I'm making the point that in the particular case of this specific work, the bias clearly comes from the data.”

This to me is a response in the form of "No, I did not meant that, clearly I meant this," and this seems to me like a defensive and rather hostile way to respond, in any response to criticism. It's a direct dismissal of Dr. Gebru's criticism, despite the interpretation that prompted it being perfectly reasonable, and does not acknowledge anything else in Dr. Gebru's statement.

-

After many tweets discussing bias in Machine Learning and expanding on his original point in a direct reply to Dr. Gebru -- an expert on the subject -- Dr. LeCun concludes with

"Post-scriptum: I think people like us should strive to discuss the substance of these questions in a non-emotional and rational manner. "

and

“It's also important to avoid assuming bad intent from your interlocutor.”

To me, this suggests the underlying message “I was perfectly reasonable, and you are being irrationally negative towards me, and should calm down”. This is once again defensive and dismissive even though Dr. LeCun's response does not address most of Dr. Gebru's statement.

In summary: if I am corrected by someone on a point, especially if that someone is an expert on the topic, I strive to listen to their point and acknowledge the cause for criticism (even if it was just due to ambiguous wording). It's easy to want to defend yourself, and sometimes appropriate, but acknowleding and listening should still be part of the response. I feel that was missing here, and this is important to point out because of Dr. LeCun's stature in this field and the potential for others to emulate his communication practices. A better response might have been a simple "It was not my intent to suggest that, thank you for pointing this out."

I avoided the use of Mansplaining and Tone-Policing in writing this because I think using them would prejudice some to not be able to consider this perspective, although I do think they are appropriate descriptors in this case. I hold immense respect for Dr. LeCun and Dr. Gebru and once again make no claims about them personally here, but only what I have said concerning this particular exchange.

Regardless of whether agree with the criticisms directed at Dr. LeCun in this case, I believe all should be able to agree with the following:

Lesson 4: it is important to be able to have rational discussions of complicated topics such as bias and address disagreements respectfully. When responding to criticism by an expert on the topic in question in such a discussion, one way to be respectful is to be mindful of whether you are replying by needlessly explaining the topic back to this expert and being condescending (otherwise known as Mansplaining), or by not addressing the points made and instead criticizing an expression of emotion by the expert (otherwise known as Tone-Policing).

On the Responsibilities of AI Researchers

Another aspect of the discussion arose in response to this exchange:

Not so much ML researchers but ML engineers.

— Yann LeCun (@ylecun) June 21, 2020

The consequences of bias are considerably more dire in a deployed product than in an academic paper.

Which itself led to many responses:

Jeez. Yann, you may be right but that's beside the point. You're missing the forest for the trees.

— Alex Polozov (@Skiminok) June 21, 2020

As researchers, we often design models without consideration for bias amplification. It's not just a data issue. We then release these models for others to embed as they see fit. https://t.co/dkgJav2vVE

Another version of the “I’m just the engineer” attitude.

— Dr. Birna van Riemsdijk (@mbirna) June 22, 2020

The @ACM_Ethics Code of Ethics applies to all computing professionals. Article 1.1: “An essential aim of computing professionals is to minimize negative consequences of computing”

Please take responsibility. https://t.co/uu6zXYaXDy

I can’t disagree more. The fundamental notion of “not my problem, it’s X’s problem” when it comes to bias is all too prevalent. Bias in systems is something that should ALWAYS be considered and mitigated.

— Eric Wang (@AmateurMathlete) June 22, 2020

To shrug and punt is an act of inexcusable tone deafness and privilege.

I've talked about why this is wrong before - the political decisions of CVMLAI researchers have political consequences on professional and hobbyist development, and end users. CVMLAI research practices make racist AI not just possible, but inevitable. https://t.co/GXqGy6WZNk

— Audrey Beard (@ethicsoftech) June 22, 2020

https://t.co/QnRwqufcoU

— Angelica Parente, PhD (@draparente) June 21, 2020

This response is nonsense and minimizes the impact and power research has on how tech is deployed. More dire in deployment? I guess, but if researchers publish something that works but is ethically questionable, ppl will still use it. https://t.co/cN0clvzL3B

Once you know there is a problem it's bad science to ignore it for future algorithms. ML is in many respects engineering - separation isn't appropriate. When harms of CFCs to the ozone layer were discovered we didn't leave it to refrigerator manufacturers to solve the problem.

— Michael Rovatsos (@razzrboy) June 22, 2020

“It’s the methodology, stupid”. ML engineers get their methods from ML researchers, so ML researchers have the ethic responsibility of showing at least how biased they are.

— Hector Palacios (@hectorpal) June 22, 2020

While others noted that researchers to some extent have to use flawed datasets to make progress:

Totally non-controversial. Surprised at the reactions here. Researchers are going to need to use the "biased" datasets to benchmark against previous research. I think as long as they note this bias in their research, they can't be responsible for every downstream implementation.

— Lux (@lux) June 22, 2020

"I guess I'm in that camp that's just a little bit confused about where and how to proceed. I'm getting anger and frustration but no clear, pragmatic recommendations of how to remedy that. The reality is that data acquisition is hard, and it can (and often is) incredibly expensive. If we required every researcher to acquire specific datasets, then ML research would inevitably suffer. I don't see how we can avoid what amounts to convenience sampling in the short-term.

So, is the suggestion that models/papers should be explicitly labeled as: (a) trained on a convenience sample not representative of real-world conditions and (b) "use at your own risk" due to bias? Personally, I think those two qualifiers would be sufficient for continuing research while taking some effort towards addressing your criticisms."

-Source

With the above coming from a more extensive discussion on reddit. Others replied noting that researchers definitely can take concrete actions to conduct their research more responsibly in light of bias in existing datasets:

"I understand that. Trust me, I have to justify my research funds to people with Bschool degrees. I would never say that collecting good data sets is easy.

But you can’t use bad data sets, pretend that they’re not bad, and expect people to not call you out on it.

Some concrete things you can do that’s more than “ignore the problem” that doesn’t cost any money:

1. Weigh samples to correct for disproportionate representation in data.

2. Do an ablation study comparing the impacts of different weighing schemes on both to-the-data accuracy and measures of bias.

3. Evaluate and be open about the extent to which your algorithm exhibits undesirable biases.

4. Discuss how your algorithm may need to be modified to be put into production.

5. Conjecture as to the effects of latent hidden variables that skew your results.

6. Consider bias, including data collection bias ("our data comes from Stanford students and so extremely over represents rich people"), bias caused by discrimination ("the credit scores of black people are non-representative of their likelihood of repaying a loan"), and bias caused by your algorithm ("As we are optimizing the median accuracy and South East Asians represent only 4% of our data set, the algorithm is not rewarded for increasing performance on South East Asians"), when giving causal stories about your algorithm."

...

-Source

"Every other field of research is able to do this, why is ML somehow not able to? When I worked in the lab, if we had any bias in our participants, it was made very clear as a caveat in the published data. Because of participant pools, data collection bias are still skewed, but it's at least acknowledged as a problem and attempts are made to rectify it."

-Source

Dr. LeCun also later addressed this topic in a quote for the article "What a machine learning tool that turns Obama white can (and can’t) tell us about AI bias":

“Yann LeCun leads an industry lab known for working on many applied research problems that they regularly seek to productize,” says [Deb] Raji. “I literally cannot understand how someone in that position doesn’t acknowledge the role that research has in setting up norms for engineering deployments.”

When contacted by The Verge about these comments, LeCun noted that he’d helped set up a number of groups, inside and outside of Facebook, that focus on AI fairness and safety, including the Partnership on AI. “I absolutely never, ever said or even hinted at the fact that research does not play a role is setting up norms,” he told The Verge.

On the other hand, in "There Is No (Real World) Use Case for Face Super Resolution" Dr. Fabian Offert argues that the model could have been evaluated without using this dataset in the first place:

the problem is this (from the Duke press release):

While the researchers focused on faces as a proof of concept, the same technique could in theory take low-res shots of almost anything and create sharp, realistic-looking pictures, with applications ranging from medicine and microscopy to astronomy and satellite imagery […].

Why faces then? Nothing good ever comes from face datasets, as Adam Harvey’s megapixels project reminds us. Deep learning has opened up a plethora of amazing possibilities in computer vision and beyond. None of them absolutely depend on (real world) face datasets. Yes, faces can be nicely aligned. Yes, faces are easy to come by. Yes, generating realistic faces is more impressive than generating realistic, I don’t know, vaccuums (to just pick a random ILSVRC-2012 class). The responsibility, however, that comes with face datasets, outweighs all of this. Malicious applications will always be, rightfully, presumed by default.

Based on the above, as well as building on Lesson 2, we can conclude:

Lesson 5: the actions of AI researchers help set the norms for the use of AI beyond academia. They should therefore be mindful with regards to which datasets ought be used to test their models, and when making use of flawed datasets can still take concrete actions in their research to minimize harm caused by doing so.

On the Value of Carefully Phrasing Claims

In response to a question regarding the motivation for the initial tweet, Dr. LeCun expressed that his aim with the initial tweet was to inform people of the issue that caused the bias in the model:

Because people should be aware of this problem and know its cause so they can fix it.

— Yann LeCun (@ylecun) June 21, 2020

Which again led to questions regarding the validity of the initial claim:

Yes. It is increasingly evident that we can’t solve all these challenges without studying an intervening in the larger sociotechnical system that surrounds the use of algorithms.

— Mark Riedl | BLM (@mark_riedl) June 21, 2020

Based on all the discussion that arose from Dr. LeCun's first statement, including Dr. LeCun's own set of clarifying follow up tweets, I think it's fair to say that it addressed a complex topic in an overly simple way and resulted in more confusion than clarification. The follow up statement regarding the responsibilities of AI researchers likewise addressed a complex topic in a very simple way, resulting in this reply:

Yann, I say as someone who has known and respected you for more than a decade: As a leader in the field, you must speak about these issues, but you must, MUST speak more carefully than this.

— Charles Sutton (@RandomlyWalking) June 21, 2020

Therefore, it seems appropriate to conclude with this:

Lesson 6: when addressing a complex topic, try to be mindful of your wording and message, especially if you are leader in the field and your statements will be read by many. An ambiguous statement can result in people taking away the wrong conclusions rather than gaining greater understanding.

Conclusion

These are the lessons I believe can be drawn from this set of events, and that I think are important to take note of going forward. Although the discussion was messy, perhaps it resulting in these lessons could mean that it was still fruitful.

Author Bio

Andrey is a grad student at Stanford that likes do research about AI and robotics, write code, appreciate art, and ponder about life. Currently, he is a PhD student with the Stanford Vision and Learning Lab working at the intersection of robotics and computer vision advised by Silvio Savarese. He is also the creator of Skynet Today, and one of the editors of The Gradient. You can find more stuff by him at his site, and follow him on Twitter.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank several friends and my fellow Gradient editors for offering their thoughts and suggestions for this piece. Also, thank you to anyone who took part in the discussion that led to this post; if anyone prefers their contribution be removed, please contact me on Twitter @andrey_kurenkov .

Citation

For attribution in academic contexts or books, please cite this work as

Andrey Kurenkov, "Lessons from the PULSE Model and Discussion", The Gradient, 2020.

BibTeX citation:

@article{kurenkov2020lessons,

author = {Kurenkov, Andrey},

title = {Lessons from the PULSE Model and Discussion},

journal = {The Gradient},

year = {2020},

howpublished = {\url{https://thegradient.pub/pulse-lessons/ } },

}

If you enjoyed this piece and want to hear more, subscribe to the Gradient and follow us on Twitter.